FOR A FARSI VERSION, CLICK HERE.

Today, when we revisit and investigate our past architectural monuments with our current knowledge and experiences, we often encounter some problems. As the current Iranian academic knowledge and professional experience in architecture

Particularly, in the field of Interior Design, it is more difficult to operate within frameworks defined by the past architecture than the modern one, placing the designer and architect in an intricate position. But, what do we mean by substantive differences between Iranian and Western Architecture and what has complicated the reconciliation and merging of these two?

Although these differences are fundamental at first glance, they are not visible and tangible. In the Western worldview, the space is often dissectible to elements such as ceilings, floors, walls and openings. This implies a functional approach to the space, more than a metaphorical one. It means, for instance, each house must have a ceiling to be protected from the rain and sun or the wall is used as an element to separate the spaces. In other words, in the tradition of Western architecture, the basic elements such as floor, ceiling, window, and wall are not significant, per se, until when an architect or a resident of the house adds something to them. In this way, the beauty is pinned to the wall, floor, and ceiling; for instance, by hanging a luxurious chandelier from the ceiling or a painting on the wall and so on.

On the other hand, in the tradition of Iranian architecture, the ceiling plays an important role; since beyond its function, it carries the metaphorical meanings. In that sense, the ceiling was interpreted as the ‘Asemaneh’ (empyrean) with its opening in the center, the so-called Horno; this means in the poetic and imaginative view of Iranians to the space, the ceiling should become an alternative for the firmament wherein sun, moon, and stars are present. Thus, the ceiling is complete and beautiful, until the extent that it does not accept easily any extra elements or at least it is the geometry of the ceiling which defines where a chandelier can be hanged. Naturally, a ceiling, which since the beginning is designed within such a vision, puts a modern designer, educated in a different logic and view, into constraints. Perhaps, in such a condition, to be able to play a role, a designer should become familiar with a different aspect of creativity.

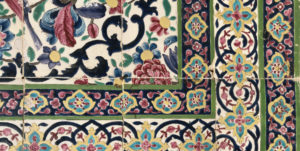

In Western view, a wall is typically a neutral background allowing the interior designer to make compositions, reduction, and additions. However, in the past vision of Iranians, a wall enjoys the geometrical and visual perfection until the extent it doesn’t allow any extra addition. The ornamentations of a wall or ceiling, including mirror-work, plaster-work, and even tile-work, allow for refining and disembodying the wall and ceiling, as if the perfection and beauty can appear only through ‘reducing’ and ‘refining’ and not ‘adding.’ Hence, ornamentations show themselves in a tight union with walls and do not intend to appear as being ‘additive’ and ‘extra.’ Doubtlessly, if today the designer, unconcern with these metaphorical aspects, manipulates and designs the space, this means he/she has acted against the principles of Iranian architecture.

Similarly, in contemporary architecture, windows are not important. Indeed, windows should manifest themselves as little as possible in order to allow a realistic view of the outside or they should not prevent the light entering inside. While in tradition of Iranian architecture, windows have a significant existence; the window calls, “look at me!” and if we wish to view outside, we should slide the sash of the window. Windows with stained-glass and geometric lattice-work are just like a filter that doesn’t let the light in, as it is; instead, it gives the light a poetic facette and makes it more imaginative and delicate.

In Western architectural experience, the floor does not play any role in composing the space; it is the interior designer who decides according to his/her own taste where to locate everything. In the Iranian view towards space, the meaning of the floor is merged with the carpet. It is the floor, covered with carpet, which can draw the meaning of ‘silence at home’ close to ‘dwelling in a blooming garden’ more than any other element and it repeatedly reminds us of the eternal paradise.

The interplay of the floor and carpet is so important that spaces are designed based on carpet size and not the opposite. Carpets are not just simple floor covers, since spreading out a carpet requires some special practices during one’s whole life. The carpet communicates a spatial order and hierarchy and defines the importance of each specific location in the space and everything else within the space. The carpet gives a significant role to the center of a room as it makes the room assemble around itself.

This substantive difference in design process makes the job more difficult for the modern interior designer, especially, if he tends to be faithful to those past principles and supposes avoiding an unconditioned architectural creativity, while the reality is something else. The past architecture has not blocked the creativity; rather, it presents a different definition of it. Creativity is not only about inventing; it does not engender and create things out of nothing. It is not only to imagine things on a neutral background; rather, it is about playing a new song on an already existing musical instrument.

Creativity means to speak new things by relying on existing principles and orders, provided for us by former experiences and not to desolate and destruct whatever is pre-existent. In this regard, creativity turns the limits and restrictions into opportunities and possibilities and this is what has frequently occurred in Iranian architecture. Following the same tradition does not mean to arrive to the same result in design. In fact, in our past architecture, not any two designs were exactly the same and falling into repetition was perceived as being despicable.

If we look at our traditions like an old newspaper, only suitable to be used as a scratchpad to add notes on its blank spaces, naturally traditions seem to be cumbersome. Thus, we prefer to deal with them as little as possible, as if in an old newspaper used as scratchpad we might prefer to have more blank space to fill them up. While, if we imagine tradition as a precious letter written by a dear person in the past who addresses us with full knowledge about us, then creativity means we should fully understand the tradition and compensate for its weaknesses gracefully and decently.

Two issues threaten our debate on tradition and referring to the past architecture; the first one is to align with obscurantism incapable of innovation. It looks backward and adorns anything related to the past. Such a trend, specifically in interior design, might tend to turn a house into storage full of antiques. The second threat is to simplify our view to the past only to decorations. This means to rely purely on appearance of the elements and decorative abuse of motifs, designs, and colours, without any effort for understanding the deeper meanings and interpreting them. In the first case, we reduce the meaning of ‘tradition’ or ‘oldness’ to ‘obsolescence’ and then we depreciate the past architectural experiences. In both cases we have been like a ‘thief with a light,’ meaning even if we praised Iranian architecture, we have also debased its principles! Beyond these two views, an approach is precious and proper that, besides aligning the traditional path, it reinterprets it in a new and fresh way. This specifically is relevant for today. More than any time, today we need creativity along our traditions.

It should be noted that, despite today’s common understanding, ‘oldness’ does not contradict with being modern, nor does tradition. It’s the ‘obsolete’ that is in conflict with ‘newness’. Ironically, becoming modern is a fundamental principle in continuity of a tradition; just like the life of a tree that comes back in spring, this ‘becoming new’ shows that the tree is alive and it lives. When we look at Iranian architecture, it is evident, for example, while in following its past architectural tradition, the Safavid architecture is in congruent with that of the Timurid period, yet they are different in various aspects. In this process of ‘becoming new’, the Safavid Architecture has developed and employed different techniques, spatial organization, as well as ornamentations compared to its precedent.

Among the publications on the field of Iranian architecture, the present book is one of the few which reflects deliberately and specifically upon the interior design. Although perhaps several magazines and journals have dispersedly and occasionally included such a topic in some of their issues, they often have not entailed such a coherency, characteristic of this publication. This book includes a series of new experiences which, in one way or another, concern themselves with the dialogue and assembly between new lifestyles and the old architectural principles. I hope this valuable book motivates those readers who are in search of ways to uncover the veils in front of the values of Iranian architecture.